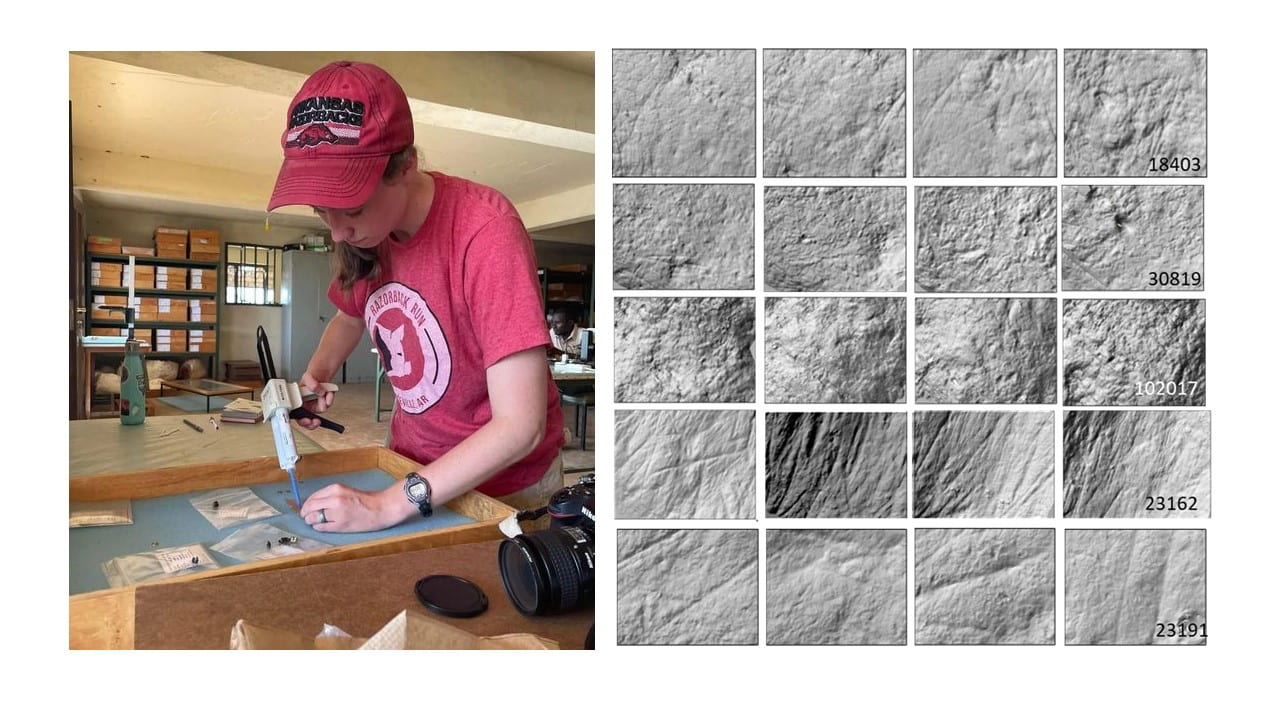

Dental microwear of fossil mammals from the late Oligocene through early Pliocene of the Turkana Basin, Kenya

Team Members: Leah Fehringer, Peter Ungar, Members of the Turkana Miocene Project

Funding Source: US National Science Foundation

This project is part of the larger Turkana Miocene Project (TMP), coordinated through Stony Brook University. More information about the TMP can be found here.

The principal goal of the project is to document relationships between abiotic and biotic elements of the basin over deep time to better understand the evolution of mammalian communities over the course of the Miocene Epoch. Our part of this work involves dental microwear analysis of fossil mammals recovered from the sites of Topernawi, Buluk, Loperot, Locherangan, Lothagam, and Napudet. Our goal is to contribute to a better understanding of mammalian paleocommunity ecology in the Turkana basin from the late Oligocene to the early Pliocene; particularly regarding food choice in the context of deep time environmental change. Most work to date has focused on the primates from these sites, but we’re working on other herbivorous mammals too, from hyracoids to ruminants and pigs rodents.

Anterior tooth use in Plio-Pleistocene hominins

Team Members: Lucas Delezene, Fred Grine, Peter Ungar, Mark Teaford, Paramita Choudhury

Funding Source: LSB Leakey Foundation

Our research group has focused largely on using molar microwear to infer the diets of the early hominin, and we have published this work widely over the past decades. Much less work has been conducted on anterior dental microwear, despite differences in the sizes and shapes of the front teeth and retrodicted differences in incisor and canine use between individual species in eastern and southern Africa during the Plio-Pleistocene. This ongoing work uses dental microwear texture analysis to infer diet-related canine use in Plio-Pleistocene hominins. Our goal is to compare hominin microwear with that of extant anthropoid primates that use their canines for a variety of ingestive behaviors.

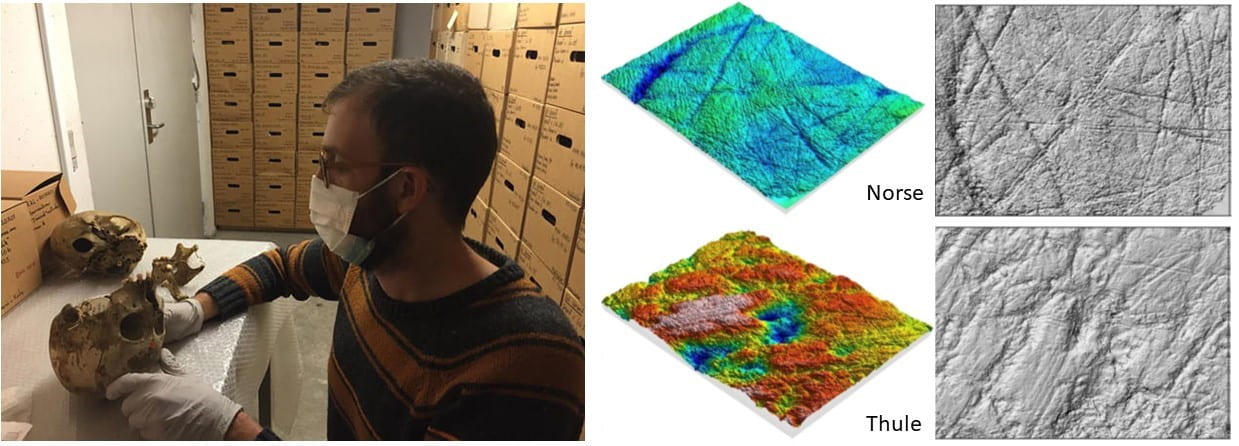

Microwear of Norse and Thule inhabitants of Greenland

Team Members:

Naseer Nassem, Peter Ungar, Lucas Delezene

Funding Source LSB Leakey Foundation

The fate of Greenland’s Viking settlements remains a topic of intense debate among archaeologists and historians. Why did they disappear whereas the Thule survived and thrived to become today’s Greenlandic Inuit? We are comparing dental microwear patterns on the molar teeth of early Viking and Thule settlers at sites from around Greenland. The goal is to determine whether there were differences over time and space, both within and between groups, in diet that might contribute to the discussion.

Dental microwear of Eocene and Oligocene primates and hyracoids from the Fayum Depression, Egypt.

Team Members:

Peter Ungar, Erik Seiffert, Steven Heritage, Matt Borths, Lindsey Lowe, Hannah Carrisalez

Funding Source LSB Leakey Foundation

The transition from the Eocene “hot house” to the Oligocene “ice box” was marked by dramatic global climate change that is believed to have led to major restructuring of mammalian communities. This project involves a dental microwear analysis of fossil primates and hyracoids from the Fayum that lived before (~37 mya), during (~34 mya), and after (~30 mya) the transition to infer diets to help us understand responses of these mammals to the intense climate change occurring at the time. And what a remarkable time it was for mammalian evolution. Fayum hyraxes were up to 1,300 kg (living ones are about 2 kg), and higher (anthropoid) primates during the Eocene were as small as 275 g during the late Eocene!

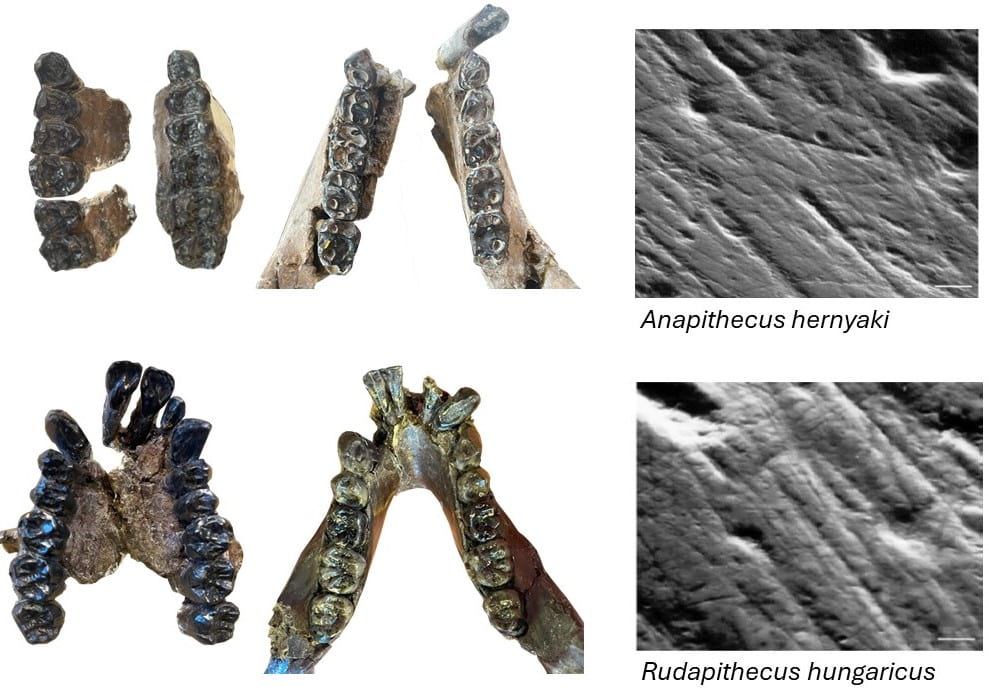

Dental microwear of Miocene primates from Rudabánya, Hungary.

Team Members:

Peter Ungar, Katie Wilcox

Funding Source University of Arkansas Honors College

Today Rudabánya is a small town in the Carpathian basin of Northern Hungary. But ten million years ago, it was a sub-tropical swamp forest on the north shore of the great Pannonian Sea. At least two species of primate, a primitive stem taxon called Anapithecus hernyaki and the great ape, Rudapithecus hungaricus, have been found at the site, along with the fossil remains of many other animals. This project aims at using dental microwear to better understand how these primates made use of the forest at Rudabánya to earn a living. This project is part of a new effort to better understand paleoecology of higher primates from Miocene of Europe and Anatolia with David Begun and Thalia Burden of the University of Toronto.

Dental microwear of Pleistocene hominids from mainland southern Asia.

Team Members:

Yaobin Fan, Leah Fehringer, Wei Wang, and Peter Ungar

Funding Source China Scholarship Council

Orangutans are the only great apes in Asia today, and they are limited to small, relict island populations on Sumatra and Borneo. During the Pleistocene, however, fossil orangutans and their relatives were much more widely distributed, from southern China through mainland Southeast Asia. How did they adapt to changing climates and habitats of the Pleistocene and pressures from humans and our ancestors? How does this translate to the exirptation of great apes from the mainland? And can this information help us with conservation efforts today? We are beginning to address these questions with the reconstruction of diets of Neogene hominids from southern China using dental microwear texture analysis in this collaboration between the Ungar Lab and the Institute of Cultural Heritage at Shandon, University.